SOCIAL LIFE IN BUCA IN THE OTTOMAN ERA

SOCIAL LIFE IN BUCA DURING THE OTTOMAN PERIOD

1. Preface

To date, there have been various studies on social life in Izmir. However, there is very little information about the surrounding settlements of Izmir. In the past, people from many different nationalities lived in relatively large settlements such as Buca, Bornova, Karşıyaka, Seydiköy and Göztepe, which were known as the villages of Izmir, just like in Izmir. In addition to Anatolian peoples such as Armenians, Jews, Greeks, Assyrians and Turks; Europeans (Levantines) also came and settled in the region over time.

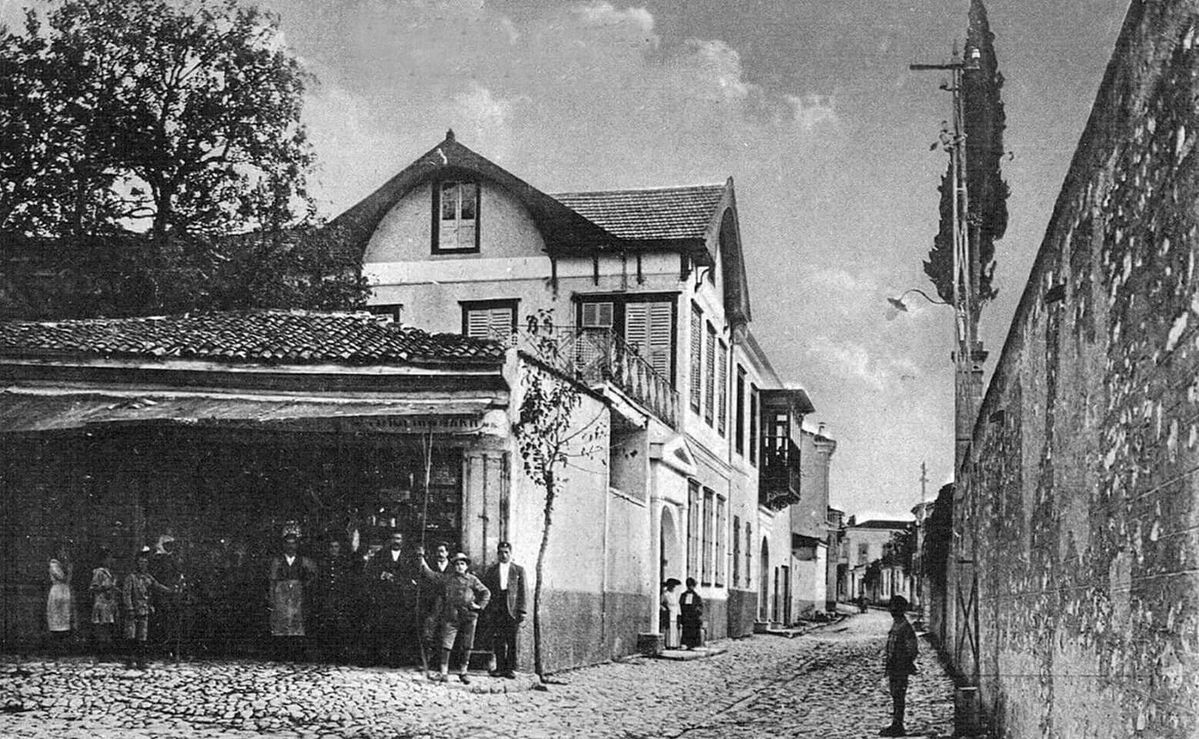

Especially from the beginning of the 19th century, a cosmopolitan structure emerged in Buca, as in the surrounding settlements. Although the population was mostly Greek, there were a significant number of European families. There were also Turkish, Jewish, Circassian and Armenian populations, albeit in smaller numbers.

Ottoman sources consist mostly of official documents and do not provide much information about daily life. Therefore, if it were not for the notes taken by Europeans, we could only guess about the history of Buca today. Fortunately, in this way; By scanning German, Dutch, French and English sources and, albeit to a lesser extent, Greek and Turkish sources, we have some basic information about daily life in the village of Buca during the Ottoman Period.

2. The First Residents of Buca: Buca Greeks

It is known that the founders of Buca were Anatolian Greeks. The Greek population here differs from the Greeks in Greece in terms of their traditions. Although it is known that there was a Greek population that settled in Buca from the Peloponnese and Aegean Islands over time[1], the traditions, songs, dances and clothing styles of the Greeks reflect Anatolian traditions. In the book titled "Anectodes of the Family Circle" published in 1836, extensive details about a wedding held by the Greeks of Buca were mentioned. In the book, it is stated that the bride and groom each wore a wedding ring, the wedding ceremony continued at the groom's house after the church, melodies were played with musical instruments and people accompanied it, and all the Greeks in the village attended the wedding. The author states that this entire ceremony resembles the figures on Greek vases and statues that are two to three thousand years old. From here, it establishes a bond between the Greeks of Buca and the ancient Greek people. It does not seem possible today to know how strong this bond is. What is certain is that, as can be understood from what has been said, Turkish and Greek traditions are surprisingly similar to each other. According to the author, the ceremony continues as follows: When they arrive home, the bride sits in the corner of the room, in the place reserved for her. He doesn't say a word and stands motionless. She does not react to the fun and only whispers to some ladies she knows next to her. There is a wreath made of flowers on it. She wears a veil made of cloth, but her face is exposed. It reaches up to the tulle belt. The bride is wearing a tinsel made of gold. Dances continue from noon until midnight. Guests coming to the wedding leave money in the bride's lap, depending on their financial situation. The bride puts the money in a small silver box. The dancing does not stop even for a minute, and the tired guests are replaced by new ones. The favorite dance of the Greeks, "Romaika", is played. The guests direct the game by forming a circle and waving handkerchiefs. As soon as one of the musicians showed signs of fatigue, a guest took a small coin from his pocket, wet it between his lips and stuck it to the musician's forehead. Afterwards, he offered wine and the game continued with the same vigor. The song is usually backed by a single voice. The author says that the wedding meal was served afterwards and that the meal included a Turkish dish, keskek, and a large bowl of rice, which Turks and Greeks generally eat at weddings. A carpet is spread on the floor for meals, and the meal is eaten by sitting in a circle. In the following hours, the bride and groom are sent to their rooms for the wedding ceremony and are given a glass of wine accompanied by traditional prayers to prevent bad luck. After the meal, the carpet was removed and the dancing continued. The wedding lasted exactly three days and the bride was not allowed to leave the house for a week.[2] As you can see, this wedding performed by the Greeks of Buca is very similar to Turkish weddings. This similarity is undoubtedly the result of Greeks and Turks living together for centuries. For example; The cultural similarity between an Aegean Greek and an Aegean Turk is greater than the cultural similarity between an Aegean Greek and an Athenian Greek.

A depiction of a Greek bride from Buca, made in the 1830s

A depiction of a Greek bride from Buca, made in the 1830s

For the Greeks of Buca, religion is also of great importance in their lives. Religious ceremonies have an important place in births and deaths, as well as in weddings. One of the ceremonies described in detail on this subject is a Greek baptism. Accordingly, Greek priests come to the house for baptism, and the sextons accompanying them carry the pulpit and the container. He places them in the middle of the room and fills them with water, olive oil, incense and a small candle. The priest reads the prayer, burns the incense and pours olive oil on it. He takes three pieces of paper, the papers are soaked in the baptismal container, and then the baby, who is a few weeks old, is brought and wrapped well with paper. The priest reads a prayer for ten minutes. Then, holding the child by the neck, he dips it into water three times and takes it out. According to the author, all expenses of baptism are covered by the godfather. The godfather's responsibility is not for show. He/she takes care of the child's education and also helps the parents if they need it. He is now at the level of his mother and father's sibling. He is also considered the child's uncle. It is assumed that they are related by blood. The godfather is no longer allowed to marry even the mother's or father's sister. Before marriage, most young men either act as godfathers or cover some of the expenses of a couple during their marriage. This situation is considered an honorable situation for the individual.[3]

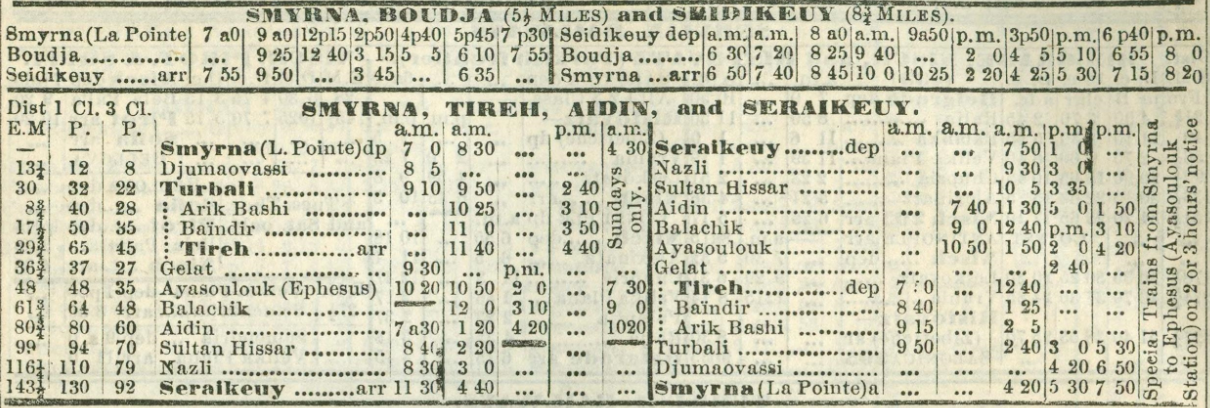

It is understood that Greek and Turkish music have been similar to each other in a melodic sense for a long time. The names of Izmir and surrounding settlements are mentioned in many Greek songs that are still known today. In many love songs, girls from Izmir, Bornova or Buca are mentioned or the modern settlements of Izmir are mentioned. The main instruments they use to make music are violin and dulcimer, which are widely preferred among the Greeks in the Aegean Region. The lyrics of a love song about Buca that has survived to this day are as follows:

As mentioned above, the surrounding settlements of Izmir have often been the subject of songs. Of course, Buca Plain is one of the places in Izmir that are the subject of Greek songs with its beauty. The lyrics of a Greek song in which the names Buca and Kozağacı are mentioned are as follows:

Of course, in Buca, as in all of Anatolia, music is often accompanied by folk dances. As a folk dance, it is obvious that the local people play the common dances of the Aegean Region, played by both Turks and Greeks, especially zeybek and kasap havasi. Likewise, the Swedish traveler Frederic Hasselquist, who came to Izmir in 1749, describes the dance performed by fifteen Greek women at a dance meeting attended by Europeans during his trip to Buca: "The woman at the head of the group directs the game by waving the handkerchief in her hand." The game meant here is probably also the same. It is the butcher atmosphere that was passed on from the Greeks to the Turks. Hasselquist later states that the game is very similar to the figures on an ancient marble relief, and thus he speculates that the local traditions date back to the Ancient Age.

No detailed information has been found regarding the clothing of the Greeks of Buca, but it is known that they did not wear fez like Turks and Armenians. Greeks are more integrated into the West than other Anatolian peoples. Especially since the 19th century, many Greek men began to wear shirts, jackets and trousers. Eastern clothing such as shalwar has been largely abandoned. An important piece of information that gives a clue about the clothing of the Greeks is about a picnic that probably took place in Kızılçullu in the 1800s. The British writer who wrote the article explains the following: "Last evening, the officers of His Majesty's warships in the harbor organized a big picnic in a romantic place called Great Paradise. A large group of young girls came from Buca, Izmir and Bornova, one after the other, on donkeys, mules and horses, or walked on foot to fill this place. Along the way, young ladies from Izmir were seen coming here in a hurry, passing through the fields on horses. Among these ladies, some of whom wore nice-looking little headdresses with tassels and gilded gold, mixed with red, some purple, and some blue silk, some very beautiful women stood out. There were many beautiful Greek girls among them, but they were all dressed in European clothes. None of them wanted to wear their short embroidered jackets, traditional Greek clothing. They probably thought that this would be considered vulgar in such a community. Before the dance, various walking parties were organized in groups to visit the ancient corners of the environment.''[4] As can be understood from here, Greeks prefer Western-style clothing. However, it can be interpreted that they continue to wear clothes that reflect Greek culture in their private lives. E. W. Schulz, in his book dated 1851, says that the Greeks of Buca were poor in appearance. However, he adds: "However, the Greek villagers do not go out with the money; they bury it as a precaution."[5]

Greeks are cautious not only financially but also in terms of their security. In the book titled "Ismeer or Smyrna and its British hospital in 1855", a European visiting Buca tells the villager who takes him around with a donkey that he wants to travel around Buca, but the villager does not agree to go out of the village because of the bandits.[6] The fact that the people of Buca built their gardens in the interior, not on the road side, and that the walls of their houses were adjacent to the street shows that the people of Buca had security concerns at that time. The mention of incidents such as robbery and kidnapping in Buca in various sources confirms the possibility that the people of Buca have security concerns. In addition, most of the people of Buca belonged to the Orthodox sect. First, Greece gained independence in 1821, then Serbia and Montenegro gained independence in 1878, and Bulgaria gained autonomy in the same year. A movement was also started for the independence of Armenia. This situation created distrust between the administration in Istanbul and the Orthodox people. In addition, it was possible that problems would arise between the Muslim population who migrated from the Balkan geography to Anatolia after the lost lands and the Orthodox population. The people of Buca probably wanted to secure themselves, like many Orthodox people in Anatolia. It is obvious that the Greeks went to many places in the countryside of Buca for recreation purposes. In a source dated 1856, it is mentioned that women went to the vineyards close to the village and sat near the well, washed the grapes in the well, cooled them and then ate them. In addition, people sit in their gardens in the clean and cool air of Buca in the evenings. Some Greeks and Turks come with their flashlights and sit under the trees and play their small mandolins. It is also stated that the shepherd who goes with his donkey in front of the camel caravan usually carries and plays this instrument with him.[7] Additionally, Greeks were also organized in the field of scouting in Buca. According to the records of 1920, the number of scouts increased from 17 tribes to 880 scouts in Izmir, and a total of 70 scouts from 2 tribes were in Buca.[8] Football was also played at the local level in Buca. G. Çitas, one of the famous football players, was from Buca.[9] From time to time, matches were played between the local teams of the schools in Buca and the American College in Kızılçullu.

The turning point regarding the water needs of the people in Buca was the aqueducts built to the east of Buca to bring water from Kangöl to Buca. According to Ottoman documents, permission for this was obtained in July 1846. The expenses for bringing this water to Buca were covered by the public.[10] In this way, the people overcame the water shortage and had access to tap water. Buca is a place with crystal clear waters during this period. These waters flow even in summer. (note 1) Water is brought from hills some distance away. There is a large and deep cistern and fountain in the garden of every house. It has been witnessed that water flows uncontrollably even in the streets from time to time. From time to time, problems occur in the water connections of houses, but this is mostly due to a Greek, a Turk or a zeybek deliberately cutting the water line. Apart from this, there is never a water shortage. There are also wide and deep wells in the vineyards.[11]

The municipal organization in Buca was established in 1898.[12] Most of the municipality members were Greeks. It is seen that all of the mayors were non-Muslim until 1922. Although the security of Buca is provided by a Turkish contingent, it is understood from here that the Greeks have a say in the management of Buca. The Greeks also had their own institutions within the village of Buca. These were churches and schools. With the construction of the Evangelistria Church in 1903, the number of churches increased to three. Their own churches, where they performed their religious services, were not very big and they were forbidden to have bells in the church, but their churches did their job. Greeks burned incense in their churches. Additionally, people were tying handkerchiefs to the trees in the church garden.[13] Greeks also had their own schools for boys and girls. In addition to the schools opened by Europeans, they also sent their children to these schools. Although the Greek writer Kararas mentions that the Greek schools are of high quality in his book "Buca", it is understood that the buildings of the Greek schools, at least, are not in good condition. There is a document stating that the boys' school in Buca, which is known to have been founded in 1872, was obsolete in 1888 and a new school was built with the money collected from the public.[15] Additionally, the girls' school was moved to the garden of the Evangelistria Church in 1910, probably due to necessity.[16] There was no high school education in Buca during this period. Those who wanted to receive high school education had to go to Izmir.[17] Of course, with the opening of the American College in Kızılçullu in 1913, many Greeks who wanted to receive high school education went to the school here. However, it can be interpreted that since studying here is expensive and many Greeks from Buca cannot afford the school fees, they go to Izmir to continue their education, and those who cannot afford this cannot continue their education. Considering that the literacy rate in Turkey was very low at that time, the majority of the Greeks of Buca probably did not even have a high school level education.

3. Europeans who changed the face of Buca: Levantines

One stop of European (Levantine) families who went to many parts of the world to trade was Izmir, an important port city. These families, who settled in Izmir, had villas built in Buca for summer resorts. After a while, many European families started to live in Buca permanently. Since most of these families were wealthy, they were of great benefit to the local people of Buca. Many of them have kinship ties through marriage. Many Greeks worked as servants in the homes of these families or as workers in their companies and factories. During the same period, they also opened schools in Buca and the people of Buca had the opportunity to send their children to education here. It is known that one of these schools, a girls' school opened by the British, became famous throughout the Levant.[18] In addition, their permanent settlement in Buca led to the opening of various religious education institutions and hotels in the following years. These European families probably had a great influence on bringing water to Buca from Kangöl and providing tap water to Buca in the first half of the 1800s. Among its effects on Buca, undoubtedly the most important one is that the railway came to Buca thanks to these families.

Europeans built magnificent villas in Buca. One of these was undoubtedly the Rees Mansion in the photo

Europeans built magnificent villas in Buca. One of these was undoubtedly the Rees Mansion in the photo

Of course, it would not be right to simplify this European part of Buca by gathering it under one roof. Some are Catholic and some are Protestant. People from the British, French, Dutch, Americans and other Western societies settled here. Most European families are merchants and engage in trade. Apart from this, there are also families who came to serve in religious institutions, came to work on the railway, and even consul families. Additionally, people who do work outside their profession, e.g. There are also families who are doctors and archaeologists. Considering that European families are more prominent in Buca based on their sectarian characteristics, Europeans were evaluated according to their sects in this study.

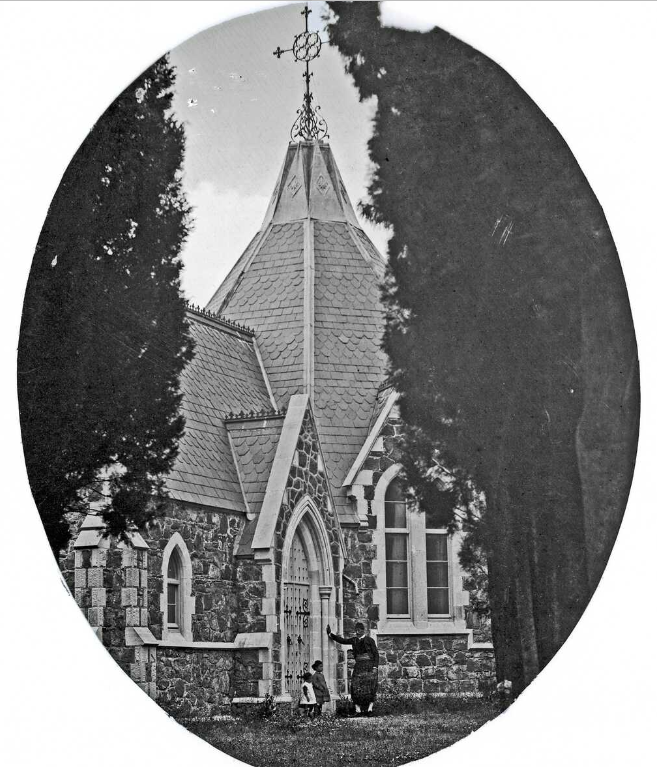

Most of the European Protestants were British and Dutch, and they were families who came to Anatolia to trade. Over time, their numbers began to increase in Buca. The fact that they founded their church in the early 1800s confirms this. This group first received financial aid of £100 in January 1837 (all aid totaling £751).[19] In 1839, they bought a house in Buca and converted it into a chapel.[20] In the following years, this small chapel became insufficient for the increasing European population, and in 1858, when they had less than five cents in hand, they started building a church. The church construction was completed in only 8 months.[21] Not only the British and Dutch, but also Protestant Germans participate in religious activities in this church.[22] In a letter written in 1842, it is mentioned that there was a "Sunday school" in Buca belonging to the missionaries, which shows that the history of religious schools goes back at least to the first half of the 1800s. According to the same letter, there are two female missionaries and a total of 13 students, including Armenians, at the school. The reason why there are so few students is that it is winter and many people went to Izmir.[23] A Protestant source dated 1847 mentions a religious school in Buca with a total of 160 students in three classes.[24]

Of course, Protestants were not the only ones who organized religious organizations in Buca. Catholics also had schools and a church with a cemetery in the garden (which does not exist today). The construction of the Catholic Church started in 1805.[25] It is thought that it took its current form in 1840, which is the date written on the church. This church was under the protection of France.[26] It is understood that Catholics organized at an earlier date than Protestants. Two of the Catholic schools were large and well-known in the area. The first one established was the Catholic Nun School, which has been operating in Buca since the 1840s. In fact, they first started operating in a small house close to the station. Between 1868 and 1871, they had to suspend education due to bandits. In 1875, a large land was purchased and a new educational building was built there. In this way, it was transformed into a boarding school and children of middle-class families could enroll there. Additionally, a day school was opened for young boys who were not yet old enough to enroll in school.[27] The second of these two famous schools is a Capuchin Monastery, founded in 1882 and whose origins date back to Paris in 1630.[28] In fact, at first the school was planned to be built on Chios Island, but when damage occurred on the island due to an earthquake, a more suitable location was sought and its construction started in April 1882 and was completed in October 1883. It is stated that afterwards, 19 priest candidates from Philippopolis and San Stefano were sent here and the training started.[29] The school had 132 students in 1892 and 93 students in 1912.[30]

Even though Buca's streets were narrow, Levantines would organize parties in their large gardens, participate in hunts, and incorporate various activities into their lives in Buca without having to go to Izmir. In addition, entertainments were organized in two famous hotels in Buca, named Alexander (note 2) and Manoli[31]. In addition, two different advertisements mention that two hotels were opened in Buca in the first half of the 1800s. The first of these belonged to Madam Aubin in the 1820s, with "elegantly furnished rooms and a beautiful restaurant", and the second one belonged to a person named Salvo in the 1840s, "where rooms were rented daily and monthly to those who wished and there was also a billiards room in the facilities". '' is a hotel.[32] There is not enough information to determine whether these two hotels are Alexander and/or Manoli hotels.

A brochure of the yoghurt factory founded in England by a member of the Defterego family, owners of the Manoli Hotel in BucaOne of the reasons why Europeans preferred Buca was undoubtedly its nature. They would go on picnics in Buca countryside, especially the Kızılçullu aqueducts and Kozağaç, for recreation purposes. Buca countryside hosted many visitors not only from Buca but also from around Izmir. The Kızılçullu region had such a magnificent appearance that it was called "paradise" by non-Muslims. The presence of the Levantines in Buca and the fame of the Buca Plain caused many famous travelers and poets to come to Buca and some even stayed here. The most famous of these was undoubtedly Lord Byron. Rumor has it that the famous Scottish poet Lord Byron engraved his name on the arches in Kızılçullu. Another poet who visited Buca was a French poet named Gustave Cirilli. After seeing Buca, he wrote a poem and named his poem "Buca". A line from his poem is as follows:

A brochure of the yoghurt factory founded in England by a member of the Defterego family, owners of the Manoli Hotel in BucaOne of the reasons why Europeans preferred Buca was undoubtedly its nature. They would go on picnics in Buca countryside, especially the Kızılçullu aqueducts and Kozağaç, for recreation purposes. Buca countryside hosted many visitors not only from Buca but also from around Izmir. The Kızılçullu region had such a magnificent appearance that it was called "paradise" by non-Muslims. The presence of the Levantines in Buca and the fame of the Buca Plain caused many famous travelers and poets to come to Buca and some even stayed here. The most famous of these was undoubtedly Lord Byron. Rumor has it that the famous Scottish poet Lord Byron engraved his name on the arches in Kızılçullu. Another poet who visited Buca was a French poet named Gustave Cirilli. After seeing Buca, he wrote a poem and named his poem "Buca". A line from his poem is as follows:

On this fertile plateau where everywhere is filled with vineyards,

As if wearing a dress with green ends,

Through its smiling villas and beautiful neighborhoods,

In the light of fireflies and among exotic plants,

You'll see young British beauties passing by here or there,

Children, protect yourself from these in Buca.[33]

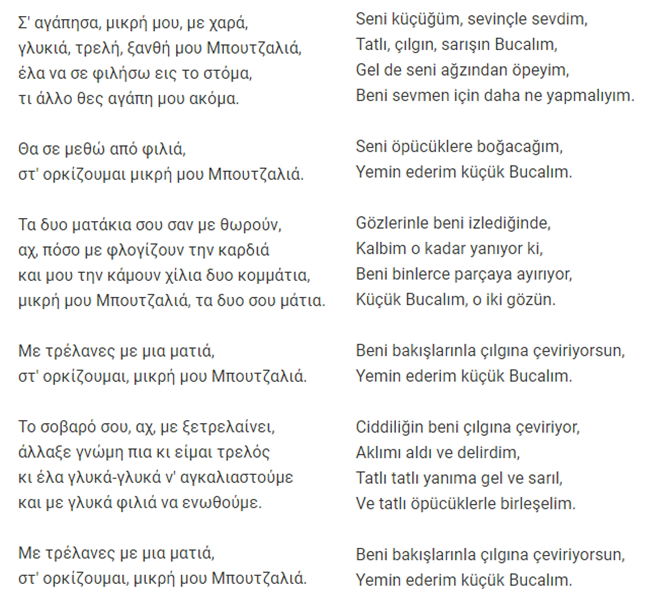

It is seen that Europeans also carry out sports activities in the Buca countryside. In the book titled "A Knight Errant in Turkey", it is written that there is a jogging area and a golf course at the fork of the railway line returning to Buca. Europeans came here to train and do sports.[34] Having a train line in Buca was also a great advantage for them. This is perhaps the most important reason why many European families prefer Buca. The Buca-Paradiso line was officially opened on September 4, 1970.[35] The financing of the line was provided by the families of Buca.[36] Thanks to the line, they could reach Buca from Izmir in 25 minutes.[37] Thus, they would not be deprived of the opportunity to go to Izmir and participate in activities such as theater. It should be added that there is mention of a theater activity in Buca in the late 1820s. However, this theater is performed outdoors.[38]

A railway line schedule including Buca, dated 18884. A suitable field for Buca: Archeology

A railway line schedule including Buca, dated 18884. A suitable field for Buca: Archeology

The archaeological studies carried out in Buca in the past are also remarkable. It can be commented that both local people and some researchers took part in these studies.

Some ancient artifacts found in the past show that Buca was also used as a settlement in ancient times. Spiegelthal also stated in his work "Revue Archeologie" that Buca was a village surrounded by the ruins of ancient Greek and Roman tombs.[39] In the book titled "Dust and Ashes", in which Francis P. B. Ashe, the son of Robert Pickering Ashe, who was a Protestant Church priest between 1898 and 1925, wrote his memoirs, it is written as follows: "The mill was built on an ancient burial place and years ago next to the mill There was a sarcophagus dug up. Inside they found a silver olive branch, some broken glass bottle pieces and coins. Men who dug the vineyard would sometimes find stone tombs placed on the upper part of the body, two facing upwards and one sideways.''[40] It is understood from this that this area, known as Koşutepesi today and is a park today, was used as an ancient cemetery in the past. In addition, according to the Greek writer Kararas, marble pieces, broken columns and jugs filled with human bones were found in the Kangölü and Kozağacı regions. Additionally, Byzantine coins were unearthed near the Forbes Mansion.[41] It is understood from here that the villagers of Buca were digging these areas from time to time and unearthed antique items. Maybe they were selling them to Europeans.

The most detailed study on archeology in Buca that has survived to this day is the record of two written ancient artifacts unearthed from the ground, kept in the book titled "the Journal of Hellenic Studies". According to the book, an inscription in the form of an obelisk was found in the garden of the Yukarı Aya Yani Greek Orthodox Church in Buca in 1876. 1.02m. It is 36 centimeters high at the top and 43 centimeters wide at the bottom. It is 6 centimeters thick. Its history dates back to B.C. It is estimated to be around 100 years old.[42] This inscription tells us that the history of Buca dates back to at least B.C. It shows that it dates back to 100 years. Of course, there is no evidence as to whether this settlement in Buca was evacuated afterwards, that is, there has been a settlement in Buca continuously until today. People here may have gone to other places during historical turning points such as the loss of power of Byzantium and the conquests of the Ottoman Empire. Nevertheless, these studies have shown that Buca has had a critical position since ancient times.

A tablet found in Buca in 1876Another ancient artifact found in Buca is a stone inscription found in 1913 in the possession of a Greek tobacco producer named Demetrios Kecayas. The height was noted as 43.5 centimeters, the width between 28 and 32 centimeters and the thickness as 17 centimeters. It was estimated that the stone was brought from Dardanel (Çanakkale), which was popular at that time.[43] Thanks to this study, it is understood that Buca was in contact with the outside world in ancient times.

A tablet found in Buca in 1876Another ancient artifact found in Buca is a stone inscription found in 1913 in the possession of a Greek tobacco producer named Demetrios Kecayas. The height was noted as 43.5 centimeters, the width between 28 and 32 centimeters and the thickness as 17 centimeters. It was estimated that the stone was brought from Dardanel (Çanakkale), which was popular at that time.[43] Thanks to this study, it is understood that Buca was in contact with the outside world in ancient times. A tablet found in Buca in 1913The studies done by Georg Weber, a member of the Weber family living in Buca, about the Kızılçullu aqueducts are unique. Weber researched both the functioning of the aqueducts and Kızılçullu and other waterways around it; It clarified many issues that were unknown until then. Thanks to him, many important details on various subjects such as the purpose for which the Vezirağa and Osmanağa waters arising from the Kızılçullu plains were used in the past, the route these waterways follow, and the role of the aqueducts on this route are thanks to him. He also produced maps regarding these issues. He included these works in his book "Wasserletungen von Smyrna". Georg Weber was not the only one who conducted archaeological research in Kızılçullu. In addition to the Kızılçullu aqueducts, Homer's Cave and other ancient traces in this region have also attracted the attention of foreign researchers. For example; In 1861, a temple was discovered on Mr. Hutchinson's land in Kızılçullu, near the Homer Cave.[44] This discovery shows that there was a settlement in Kızılçullu in the past.

A tablet found in Buca in 1913The studies done by Georg Weber, a member of the Weber family living in Buca, about the Kızılçullu aqueducts are unique. Weber researched both the functioning of the aqueducts and Kızılçullu and other waterways around it; It clarified many issues that were unknown until then. Thanks to him, many important details on various subjects such as the purpose for which the Vezirağa and Osmanağa waters arising from the Kızılçullu plains were used in the past, the route these waterways follow, and the role of the aqueducts on this route are thanks to him. He also produced maps regarding these issues. He included these works in his book "Wasserletungen von Smyrna". Georg Weber was not the only one who conducted archaeological research in Kızılçullu. In addition to the Kızılçullu aqueducts, Homer's Cave and other ancient traces in this region have also attracted the attention of foreign researchers. For example; In 1861, a temple was discovered on Mr. Hutchinson's land in Kızılçullu, near the Homer Cave.[44] This discovery shows that there was a settlement in Kızılçullu in the past.

One of the important archaeological artifacts found in Buca is a strange-looking human figure that was cut and sent to England by the British ambassador M. Dennis in 1869 and is exhibited in the British Museum today. The location of this place is stated as the area around Tahtalı Mountain. Georg Weber visited this place in the following years; He described it as a hole 8-10 meters deep, 100 meters wide, surrounded by stones without mortar. He wrote that there were seats made of well-polished stone at the other end of the cave. The relief found in Tahtalı region and currently exhibited in the British Museum. The picture on the left is a drawing made in 1892, the picture on the right is the current version.5. Epidemics, Earthquakes, Bandits and Civil Disputes

The relief found in Tahtalı region and currently exhibited in the British Museum. The picture on the left is a drawing made in 1892, the picture on the right is the current version.5. Epidemics, Earthquakes, Bandits and Civil Disputes

Although many travelers boast about its weather, gardens, soil and many other features, of course, some problems have arisen in Buca from time to time. Since Buca was in a remote place at that time (note 3), it became a frequent spot for bandits. For this reason, it is stated in various sources that the bandits both trouble the local authorities and annoy the local people. In addition, there were earthquakes and epidemics in Buca. However, it was at a much lower level than Izmir, and on the contrary, many times the people of Izmir took shelter in Buca in cases of fire and epidemics. It is also seen that there are internal disagreements among the people in Buca from time to time.

Buca, with its location close to Izmir and its mountainous regions, was in a suitable location for bandits. These gangs, sometimes mixed and sometimes consisting of a single nation, generally consisted of Albanians, Turks and Greeks. In an incident that took place in 1851, a gang operating in Buca and its surroundings hid in the house of the British Werry family. The Turkish gendarmerie, who could not enter the house of Werry, who was the British Consul and had immunity, asked Werry to release the gangs, but their requests were not fulfilled. Meanwhile, the gangs opened fire on the gendarmerie and the police station, and the gendarmerie then raided the house. Two bandits were killed and one was captured. One bandit who tried to escape to the Barker family's house was caught, while the rest escaped. The people of the village, who were fed up with the gang activities in and around Buca, reacted to these two British families for not helping to solve the problem and expressed their anger because not all the bandits could be caught.[45] Shortly after this incident, Halil Pasha submitted his resignation because his soldiers entered the British Consul's house without permission.[46] In another news report dated 1892, it is stated that the bandits asked for money from Mr. Dermond, whose house was located near the train station in Buca, and then they fled when an alarm was raised in the village, and this incident caused fear in Buca and the surrounding areas.[47] In another incident, a Croatian bandit named Lucca and his gang, who is stated to be an engineer and an intelligent man who recently participated in the construction of an aqueduct in Buca, are mentioned. One day, a worker from Buca, while returning home, sees this gang hiding near the "new aqueduct" (note 4) and informs the lord. Agha sends a group of gendarmes, but in this place that Lucca knows very well, two of the gendarmes are killed and the gang manages to escape unhurt.[48] One of the known events is that in 1898, Alexander, the son of Davut Farkoh, one of the owners of the Bucalı ferry company, was kidnapped to the mountain and ransom was demanded.[49] One of the noteworthy notes is that the road from Buca Tahtalı (today Resources) to Ephesus is called the "blood road" because of the bloody murders.[50] This situation once again shows that bandits and bandit gangs are frequent in the region.

Robbery incidents are also seen in Buca. In a news dated 9 November 1829, it was seen that a group of 30-40 Greek bandits entered the house of one of Buca's influential families and some valuable items were stolen. Following this incident, a unit of 150 people was sent to the region and many Greeks who were thought to have ties to criminals were imprisoned. One of these people said that this was a three-week planning. Additionally, after this incident, many Europeans went to Izmir due to security concerns.[51] In 1851, the De Jongh family's house was robbed by a gang from the village. According to the news, the group that robbed the family's house was a group of five people led by a bandit named Bibaki, and this group was aware that the family's sons and male servant were not at home. They jumped over the wall of the house, entered the house, took some valuables and escaped.[52] There is a document stating that the house of the American merchant Landi was robbed on May 9, 1854.[53]

It seems that one of the events that bothers the public is epidemics. Buca, on the other hand, was less affected by the epidemics than Izmir and Bornova. The main reason for this is that it stays in a more remote place. In the report of the book titled "Rapport à l'Académie Royale de Médecine sur la peste et les quarantaines" dated January 29, 1845, it is written as follows: "Mr. He remembers taking shelter in the village of Buca, a short distance away, clean and with adequate facilities. Some of these 14,000 people commute to Izmir on a daily basis. Plague occurs in only 10 of these villages. Despite the lack of precautions, the rest remain intact. "The bodyguards of these 10 people are not affected by the plague."[54] In another report dated March 19, 1845 in the same book, it is stated that although the plague was widespread in Bornova, Buca was not affected much by it, four tents were set up at the entrance of Buca facing Izmir and It is written that people who came to Buca from were first quarantined here for two days.[55] Again, in a cholera epidemic that broke out in Izmir in 1848, two-thirds of Izmir's population fled to Buca and Bornova.[56] In a report dated 1893, it is stated that cholera broke out in Izmir, but Buca was only slightly affected.[57]

Among the events that affect Buca, there are of course earthquakes. In the work called ''Baltische Monatsschrift'', it is stated that they go down with donkeys (around Kızılçullu); He writes that he came to the village of Buca, which has no doctor and has a wonderful atmosphere, and earthquakes are encountered frequently here. A traveler named Otto Magnus von Stackelberg will describe an earthquake in Buca as follows: "One evening, I had just gone to bed and fallen asleep when I was suddenly woken up by my bed shaking violently. I got up to see who woke me up, but I couldn't see anyone; At the same time, I noticed that the ceiling was shaking among the crashing sounds. I was frightened as if I had seen a ghost. I rushed out of the room to find Brönsted sitting at the table, terrified with fear. The boarders were also running out of the house in panic. The earthquake passed; But the fear of a more severe earthquake lasted for hours.''[58]

It is seen that there are some disagreements among the people of Buca from time to time. E. W. Schulz writes in one chapter of his book that a Church of England pastor described Greek Christianity as "a true caricature of Christianity".[59] Another notable event is that other Christians opposed the Protestants' application to have a church cemetery. Other Christian communities had already opposed Protestant church building in the early 1800s. In 1848, Armenian Catholics opposed the cemetery request. In addition, they did not raise a voice against the Catholic cemetery. In addition, European Catholics and Greeks are also disturbed by this situation. At that time, Protestants were using a house built by Bostonian Joseph Langdon for worship purposes. (note 5) However, Catholics were allowed to build a church at that time. The Catholic Church even had a bell, although it was forbidden to Armenians and Greeks. In the same year (1848), Protestants applied to use the bell of an old American steamboat in their churches. Even though the sound it made was low, those who opposed the bell either said they would lower it or wanted the pasha to intervene in the situation. British diplomats, on the other hand, were carrying out diplomacy to have both a church and a cemetery.[60] According to another source, in 1847, the bishop of the Greek Church in Izmir forbade Greek families from sending their children to evangelical churches. In another notable incident, Robert Deyon, the son of the Danish Consul, who hit a Greek woman at the Buca Fair, was lynched by the villagers of Buca.[61] In the book titled "Ismeer or Smyrna and its British hospital in 1855", it is stated that a zeybek molested a woman coming out of the Yukarı Aya Yani Church, the man wanted the woman to be his wife and said that he wanted to live in the mountains with him, and when the woman refused, the zeybek tried to kidnap the woman. It is said that he was working and when the woman started shouting, the zeybek ran away after there were people around. Afterwards, Pasha catches some men and brings them before the woman. Since the punishment would be death or imprisonment, the woman says that she cannot remember the person because she is too scared. The author of the book mentioned that zeybeks might be interested in European women after this incident and gave the following example: Again, at that time, the Pasha said that a Turkish contingent would pass through Buca and that European women should stay away from the windows and stay inside the houses.[62] Buca Protestant Church, 1872-73

Buca Protestant Church, 1872-73

(Photograph: British School of Athens)

Tensions have not always been between people, but sometimes they have occurred between the state and the people. It is understood that especially the Greek people objected to the state from time to time and some uprisings or tensions occurred, although not on a large scale. For example; There is a document dated February 15, 1887 stating that the people of the Buca district would obey the government and that soldiers would be stationed in this region.[63] In April 1889, people did not want to participate in a road work to be carried out in Buca and an investigation was conducted on this issue. This situation shows that people are sometimes forced to do forced labor.[64]

One of the striking notes about Buca is that its roads were bad at that time. It has been written that people's eyes are disturbed by the dirt road. The reason for this is that the road was not irrigated at that time.[65] According to Ottoman documents, the construction of the Kemer-Buca road would take place in 1847.[66] There is no information about whether the dust problem has been solved after the road is completed.

6. Conclusion

By giving information about social life, mostly covering the 1800s (note 6), an attempt has been made to give an idea of what life was like in a suburb of Izmir during the Ottoman Period. It can be seen that there are no major differences between life in Buca and life in Izmir. Of course, the biggest reason for this is that Buca was a settlement that was close to Izmir at that time, especially through European Levantine families and some wealthy Greeks with whom these families had strong commercial and family ties. If we look further back to the 1700s, we could perhaps see a more conservative and traditional structure that was more intertwined with Anatolia, but there are not many details about that period. We can conclude that in the 1800s and until the 1920s, an Anatolian Greek and European culture, influenced by Turkish and Islamic culture, was blended in Buca.

The most striking difference between Buca and Izmir is related to security issues. The fact that Buca was not on the main roads and was surrounded by mountains and hills during the periods when the railway did not yet exist is undoubtedly the reason why gangs and bandits strengthened their presence in this region. Of course, staying in an out-of-the-way place for Buca also had its advantages. It is seen that many people flee from Izmir to Buca in cases of earthquake, fire, epidemic and war. In addition, it will not be a surprise to see that the entertainment life in Izmir is more lively than in Buca. However, it is seen that people in Buca also participate in many activities such as horse racing, picnics, golf and hunting. It is not possible to do some of these in Izmir.

Finally, it should be noted that; Since the Armenian, Jewish, Assyrian and Turkish population in Buca is smaller than the Europeans and Greeks and little information is known about them, it is difficult to comment on how much the existence of these groups affects the social life in Buca. Therefore, it would not be correct to make an evaluation on this issue.

- Notes -

Note 1: However, the previous source mentions that there is a water shortage in Buca. There is a contradiction here, but it can be concluded that Buca's water resources are abundant but cannot be used efficiently because there is no regular system. This problem seems to have been solved with the construction of a new aqueduct in 1847.

Note 2: The hotel referred to here is probably the Lipovatz Mansion.

Note 3: It can be said that it was in a remote location at that time because it was far from the railway and the Izmir-Ephesus road.

Note 4: The new aqueduct referred to here is probably one of the aqueducts built in the 1840s, carrying water from Kangölü to Buca, in the northeast of Hasanağa Garden.

Note 5: The house probably referred to here is the house that was purchased in 1839 and converted into a chapel.

Note 6: There are almost no sources describing the 1600s and 1700s. For this reason, the 1800s and early 1900s are mostly included.

This article was created by atalarimizintopraklari.com. All rights reserved. All or part of this article cannot be used in books, magazines or newspapers without citing the source.

- Sources -

[1] Teodoris Kontaras, O Boutzas tis Smirnis

[2] Anectodes of the Family Circle, 1836, sf. 197, 198, 199, 200, 201

[3] Ismeer or Smyrna and its British hospital in 1855, 1856, sf. 287, 288, 289

[4] 19. Yüzyılda İzmir Kenti, Rauf Beyru, sf. 131

[5] Reise in das gelobte Land im Jahre 1851, E. W. Schulz, 1851

[6] Ismeer or Smyrna and its British hospital in 1855, 1856, sf. 275

[7] Ismeer or Smyrna and its British hospital in 1855, 1856, sf. 278

[8] Buca'da Konut Mimarisi (1838-1934), Feyyaz Erpi, sf. 15

[9] Buca'da Konut Mimarisi (1838-1934), Feyyaz Erpi, sf. 15

[10] T.C. Cumhurbaşkanlığı Devlet Arşivleri

[11] Ismeer or Smyrna and its British hospital in 1855, 1856, sf. 274

[12] Ihlamur ve Fesleğen Kokulu Buca, Oktay Gökdemir, 2011, sf. 43, 44, 45

[13] Ismeer or Smyrna and its British hospital in 1855, 1856, sf. 284

[14] Nikos Kararas, Buca, 1962

[15] T.C. Cumhurbaşkanlığı Devlet Arşivleri

[16] Nikos Kararas, Buca, 1962

[17] The Greek American, The Asia Minor Catastrophe, Constantine G. Hatzidimitriou, 20 Eylül 1997

[18] Veertiente Jaargang, De Gids, 1876, sf. 491

[19] The Ecclestical gazette of monthly register of the affairs of the church of England, 1839

[20] The diocese of Gibraltar; a sketch of its history, work and tasks, Henry Knight, 1917

[21] The Bulwark of Reformation Journal, 1 Ekim 1858

[22] Reise in das heilige Land im Jahre 1851 unternommen und beschrieben, 1852, Joseph Schieferle

[23] The Missionary Register, 1842, sf. 101

[24] Magazin für die neueste Geschichte der protestanischen Missions, 1847, sf. 128

[25] Nikos Kararas, Buca, 1962

[26] The Freeman's Journal, 1 Ekim 1842, sf. 2

[27] Les missions catholiques françaises au 19e siecle, Piolet Jean Baptiste, 1901, sf. 146

[28] Vereinsgaben der Görres Gesellschaft, 1905

[29] Echos d'Orient, 1897, sf. 210

[30] XX. yüzyıl başlarında Osmanlı Devleti'nde yabancı devletlerin kültürel ve sosyal müesseseleri, Adnan Şişman, 2006

[31] Bradshaw's continental steam train, 1875, sf. 663

[32] 19. Yüzyılda İzmir Kenti, Rauf Beyru, sf. 132

[33] 19. Yüzyılda İzmir Kenti, Rauf Beyru, sf. 133

[34] A Knight Errant in Turkey, Arthur Oakstone, 1908, sf. 36

[35] The Standard, 1 Ekim 1870, sf. 3

[36] The Morning Post, 1 Ekim 1870, sf. 7

[37] Bradshaw's continental rail guard, 1888, sf. 296

[38] 19. Yüzyılda İzmir Kenti, Rauf Beyru, sf. 132

[39] M. Spiegelthal, Revue Archeologie, 1876, sf. 326

[40] Dust and Ashes, Patrick Ashe, 2011

[41] Nikos Kararas, Buca, 1962

[42] The journal of Hellenic studies, W. H. Beckler, 1917, sf. 114

[43] The journal of Hellenic studies, W. H. Beckler, 1917, sf. 113

[44] The Morning Chronicle, 25 Eylül 1861, sf. 5

[45] Austria: Archiv für Gesetzgebung und Statistik auf den Gebieten der Gewerbe, des Handels und der Schiffahrt, 1851, sf. 220

[46] Mémories, Société royale de géographie d'Anvers, 1879, sf. 78

[47] Brigandage à Smyrne, Le Yıldız, 20 Kasım 1892

[48] Ismeer or Smyrna and its British hospital in 1855, 1856, sf. 252, 276

[49] T.C. Cumhurbaşkanlığı Devlet Arşivleri

[50] Turquie d'Asie, de Smyrne a Ephese, sf. 468

[51] The Times, 9 Kasım 1829, sf. 2

[52] The Morning Chronicle, 9 Eylül 1851, sf. 6

[53] T.C. Cumhurbaşkanlığı Devlet Arşivleri

[54] Rapport à l'Académie Royale de Médecine sur la peste et les quarantaines, sf. 583

[55] Magazin für die neueste Geschichte der protestanischen Missions, 1847, sf. 131

[56] The Freeman's Journal, 7 Eylül 1848, sf. 4

[57] Report of the Medical Officer of the Local Government Board for the Year 1894-95, Dr. Barry, 1896, sf. 274

[58] Ihlamur ve Fesleğen Kokulu Buca, Oktay Gökdemir, sf. 50

[59] Reise in das gelobte land im jahre 1851, E. W. Schulz, 1851

[60] Kismet of the doom of Turkey, Charles MacFarlane, 1853

[61] T.C. Cumhurbaşkanlığı Devlet Arşivleri

[62] Ismeer or Smyrna and its British hospital in 1855, 1856, sf. 285

[63] T.C. Cumhurbaşkanlığı Devlet Arşivleri

[64] T.C. Cumhurbaşkanlığı Devlet Arşivleri

[65] Shores and Islands of the Mediterranean, including a visit to the seven churches of Asia, Henry Christmas, 1851, sf. 103

[66] T.C. Cumhurbaşkanlığı Devlet Arşivleri